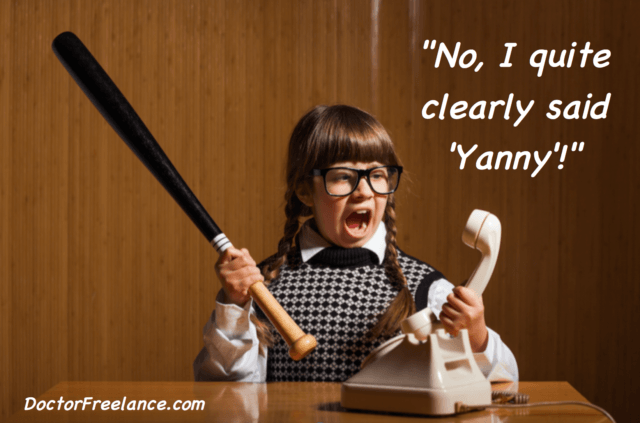

I reckon we’re about 10 minutes into the 15-minute fame run of the Yanny vs. Laurel dust-up. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, you can give it a whirl here.) I was firmly in the Yanny camp until late in the day yesterday, when I watched a video that explained the effect—after which I only heard “Laurel,” and couldn’t switch back. Weird how the brain works! In any case, I think the Yanny vs. Laurel divide offers a nifty jumping-off point to discuss client communications and the importance of perception in business.

I reckon we’re about 10 minutes into the 15-minute fame run of the Yanny vs. Laurel dust-up. (If you don’t know what I’m talking about, you can give it a whirl here.) I was firmly in the Yanny camp until late in the day yesterday, when I watched a video that explained the effect—after which I only heard “Laurel,” and couldn’t switch back. Weird how the brain works! In any case, I think the Yanny vs. Laurel divide offers a nifty jumping-off point to discuss client communications and the importance of perception in business.

When Client Perceptions and Client Communications Collide

- Our clients don’t always hear what we mean, and we don’t always hear what our clients mean. It’s the human condition. Particularly for writers and editors, we pride ourselves on communications skills—and very much on our written client communications. The challenge is, no matter how well crafted you believe your email is, there’s room for miscomprehension—especially when you’re working with a new or inexperienced freelance client. To me, it’s the best argument in favor of communicating complicated (or contentious) information over the phone or in person whenever possible. In an email, I have no way of reading a client’s reaction, whether it’s negative or positive. When a client has fully formulated their objection without my input, it’s a lot more work to set the situation right.

- This dynamic also illustrates why it’s so key to be as detailed as possible within your scope of work: “This is what I’m going to do, here’s how I’m going to do it, and here’s what it’s going to cost.” You need to be able to state the client’s understanding of the project back to them in their own terms, in a way that they agree with. If there’s any ambiguity at all, there’s room for a communication error.

- Pricing is another great example of where this type of miscommunication comes into play. We all have our preferred policies: “I charge by the hour,” “I charge by the word,” “I charge by project price,” and so on. Frankly, if your chosen method works for you 100% of the time, that’s great. But put yourself in your client’s shoes: The same end cost, relayed in three different ways, could be perceived very differently. If someone is unfamiliar with the publishing industry, for example, $1 a word for writing will sound expensive. (Many years ago, I had a prospect ask, “Does that cost include short words like ‘a’ and ‘the’?”) As readers of this blog or my books know, I believe an estimated range is the most persuasive way to convey pricing. But if a client insists that I work on an hourly basis, that’s their call, not mine…assuming I want the project.

The final point is that this underscores the importance of cultivating your relationships in general, and over the long term. Time and pressure will reveal a client who has a tendency to hear “Laurel” when you most certainly said “Yanny.” Once you understand how they’re perceiving what you’re trying to say, you have much better odds of getting it right. And when you connect with a client who’s simpatico, treat ’em like a rockstar.

In the comments: Sure, let me know whether you heard “Yanny” or “Laurel.” But more important: What are your strategies to prevent or overcome problematic client communications?

I work mostly with indie authors, so I find that I have to explain a lot. But I’ve found that type of relationship lends itself more easily to communication without so much formality. I’ve found a comfortable balance between sounding authoritative without sounding intimidating, I think.

When I’m dealing with pricing, there are certain projects I price by the word and projects I price by the hour. In each case, I give the author a general idea of how many hours will be put into it, based on previous averages. That seems to put their minds at ease that I’m not charging a high price for a little bit of work, or that I’m not going to pad my hours and surprise them with a larger bill at the end.

Sometimes it’s just a matter of saying, “I know you may already be aware of this, but in case you aren’t . . .” and proceeding from there.

Thanks for commenting, Lynda. Your approach sounds spot-on—and I really dig the concept of “authority without intimidation”!